Telling stories for justice, sustainability and hope

The first lecture in Green Templeton College’s Sustainable Education series was opened by Principal Sir Michel Dixon, who emphasised the importance of sustainability across the college and the challenges faced by the Global South due to climate change.

The keynote speaker, Professor Chukwumerije Okereke, a leading expert in Global Environmental and Climate Governance at the University of Bristol and Co-Director of the Centre for Climate Change in Nigeria, explored the theme of fairness in climate action. He was warmly welcomed back as a former Green Templeton fellow and a lead author for the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on 1.5°C

Joining the discussion, Dr Amanda Power, a historian currently writing Medieval Histories of the Anthropocene, provided insights on how history informs sustainability education.

Michael Elsy (Graduate entry medic, 2023), reports on the lecture.

The fairness debate

Professor Okereke captivated the audience through the stark statistics presented regarding the urgent need for sustainability; the equivalent of 27 football fields worth of forest are lost every minute globally, five trillion plastic bags are used each year, and, shockingly ,approximately one million species are threatened by extinction.

He touched early on the crux of the discussion: why does fairness matter? Only four countries produce approximately two thirds of our emissions, yet it is the countries with the smallest impact who pay the price. There is asymmetry in contribution, use, impact, and (ultimately) in voice. For example, it is usually the largest polluters who have most seats at the table for global policy discussions, such as the COP conferences. As a result, fewer representatives from the Global South, which bears the burden of climate change, are able to participate.

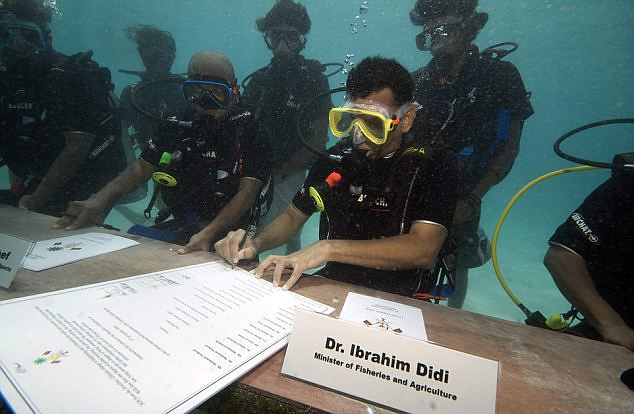

The iconic image of the Maldives cabinet having a meeting underwater in scuba gear powerfully showed the particular risk of rising sea levels to small islands, although it is perhaps disheartening that such little progress has been made since this photo in 2009.

Decolonising sustainability education

The disproportionate impact of climate change on the Global South, coupled with unequal involvement in decision-making, shows that environmental justice is essential; everyone has the right to a fair share of the Earth’s resources. Justice principles should be employed: there is historical responsibility, the polluter should pay for damage caused and help to prevent further harm, and the needs of the most affected nations must be met. Environmental justice and international collaboration are fundamental in reducing the current discrepancies in sustainability education.

There is a Global North-South divide for sustainability education. Professor Okereke compared the North’s ‘mitigation focus’ to the ‘adaptation focus’ of the South. This is also evident in the North’s ‘intergenerational justice’ as opposed to ‘intragenerational justice’ in the South. Southern countries are focused on surviving the all-too-real current effects of climate change, whereas Northern countries implement plans for future generations, perhaps due to believing that they have many years before the consequences are felt. Western-centric sustainability models, while valuable, often overlook the personal narratives central to sustainability education in the Global South.

Therefore, Professor Okereke proposed decolonising sustainability education, wherein we need to reframe sustainability beyond Western definitions and integrate indigenous and local knowledge into how we teach others sustainable practices. There needs to be humility in the North, and a willingness to adapt education approaches, in contrast to the hubris that has perhaps been previously demonstrated. This can be considered when implementing the UN’s promising Sustainable Development Goals, which aim to promote equity and fairness.

Lessons from history

Dr Amanda Power then shared her reflections on the talk. A historian who specialises in medieval religion, power, and intellectual life is a novel, and likely unexpected, guest for a climate and sustainability seminar series. However, Dr Power has also talked extensively on the use of history to study the ‘Anthropocene’s’ contribution to climate change, including in The Conversation; Times Higher Education; and on Climate in the history curriculum for the Royal Historical Society blog.

The perspective through the humanities lens was refreshing; key questions were asked. Which are the most important stories we need to tell? How do we galvanise a response to climate change? Does this change between generations and how do we implement this in schools at the curriculum level? How do we ensure environmental justice and maintain a hopeful tone without too much doom and gloom? We can definitely learn from history by focussing on the importance of repressed stories, such as how colonialism demonstrated that dominant powers shape narratives, often suppressing alternative voices.

Audience engagement

The floor was then opened up for questions, principally: (1) how we can deal with the pressure of authoritarian governments’ attacks on education, particularly sustainability; (2) how there is populist pushback to sustainability policies; (3) how we educate the top 1% who are in the driver’s seat for decision-making. These questions demonstrated the holistic approach needed for promoting sustainability education – we need to appeal to the general public, the richest in our society, and have governments that are willing to invest in sustainable futures. The main discussion points from our speakers and Dr Mark Hirons (chairing the evening) were that we need to be able to connect sustainability with livelihoods; there can be valuable lessons from the South’s storytelling approach to engage with people in the North.

Perspectives

In conclusion, we need to remain hopeful whilst championing increased sustainable education, despite world leaders taking a backwards approach to the climate emergency. For example, Donald Trump’s name was only briefly mentioned but the large, predicted negative impact of his second term as US President cannot be ignored. It was estimated in 2019 that to prevent warming beyond 1.5°C, we needed to reduce global emissions by 7.6% every year until 2030. It is still too soon to fully know the consequences on Trump’s proposed return to fossil fuel dependence, reduction in clean energy funding, and removal of protective climate regulations. However, the Climate Action Tracker indicates that at current rates, our world will warm by 2.7°C by 2100.

Despite this, we can still take individual action to reduce our individual carbon footprints, whether having a plant-based diet or avoiding flying, and campaign for change at the policy level. Transitioning from driving to walking and cycling is predicted by the WHO to save up to 5 million lives per year. Green Templeton College is committed to a sustainable future. We cannot succumb to ‘doomism’, wherein we resign ourselves to our fate regarding climate change, and we need to adapt and be open to challenging the solutions provided by those in positions of power.

Future lectures

Join us on Thursday 27 February for the next lecture in the Sustainable Education Series, where we will pick up many of themes raised here by focussing on Power and Politics. Chris Skidmore OBE, former Minister of State for Energy and Clean Growth who signed the UK’s pledge for Net Zero into law, and Associate Professor Debbie Hopkins will lead this stimulating discussion.